(test post – text blocks)

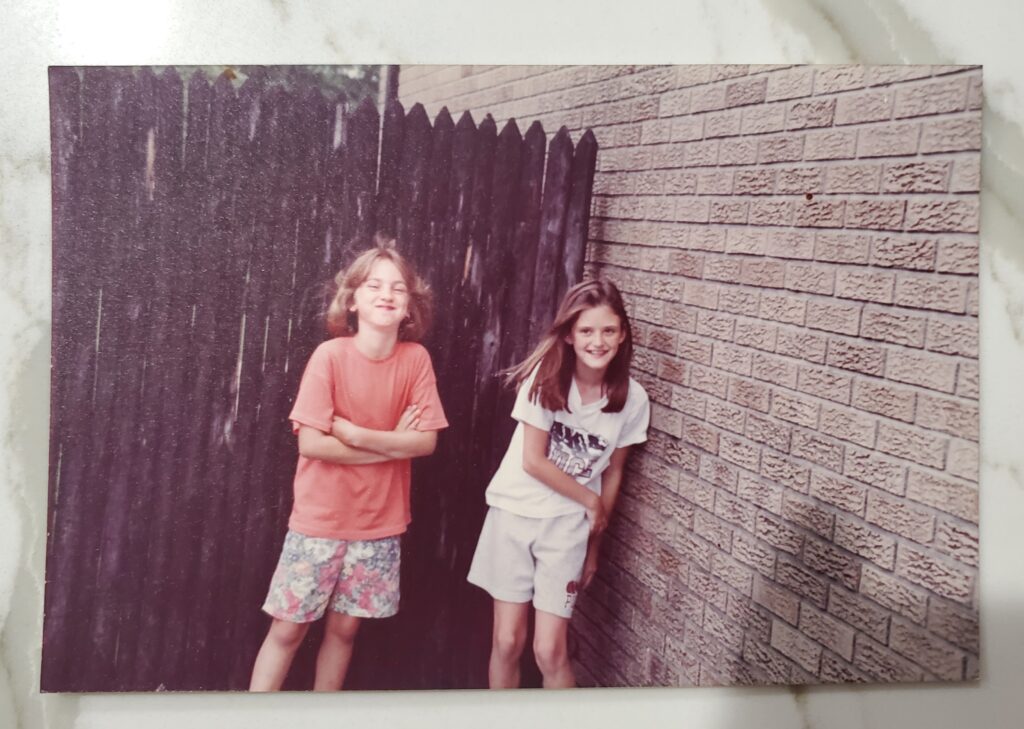

1989 – to some, it’s a Taylor Swift album. For me, it was the year that set the course for the rest of my life. One winter morning, on a school day when kindergarten was the new skin, I came downstairs to find my mother at the kitchen table, slowly lowering a newspaper. She informed me that my brother was dead. This is my only memory where I am hovering over my body, like a dragonfly watching the scene.

My cowardly father left the continent, and my mother drove me to school that day. Over the PA system, a prayer was said for my family. Instead of our usual morning story time, my teacher sat me beside her on the couch to talk to my peers about death. The confusion and fear on their small faces was palpable. I was not ready to talk about the death of my best friend, and my attempt to distract the teacher by tickling her landed me in the small wooden timeout chair.

In Visions of Gerard, Jack Kerouac described the loss of his brother during childhood as when he stopped being able to play as he turned inward with introspection. Sitting in that chair, watching everyone play while I tried to understand what was happening, felt like the beginning of that process for me. The next few years were difficult, with the dissolution of my family, schoolyard bullying, and an existential crisis propelled by schoolmates calling me “death girl.” Everyone told me to just pray, as though surrendering to an already unrighteous creator was the answer. Adults were failing me. Instead, I found mayflies.

A burrowing mayfly of the genus Hexagenia was nearly extirpated from the Windsor-Detroit area, my home in the Great Lakes. This was primarily due to contaminated sediments from industrial practices and anoxic water events decimating their populations. They had been under stress since the 1950s. In the 1970s, legislation was drafted toward remediation of the Great Lakes. Initially made to improve water quality, later amendments considered the interconnectivity of ecosystem components, broadening to include sediment quality and biological integrity.

By the early 1990s, Hexagenia populations were benefiting and showing signs of recovery. I remember this recovery being another morning on a school day. I looked out my window and everything was covered in mayflies. The grass was black. The road was squirming. I walked to the bus stop down the middle of the road where cars had crushed them down. A snow plow went down my street. I had never seen anything like it – gentle chaos. Everyone was talking about it. Few felt that their return was a miracle; many expressed disgust. I quickly became fascinated by this tiny phoenix, a small, fragile organism that lost its family, defied its own death, and came back in numbers never seen in decades. They were my Lazarus story, a real-life emergence from a watery tomb.

The mayfly, Hexagenia, is a gentle creature that barely survived us. They’re a food staple to both aquatic and terrestrial lifeforms, and we may be the only species that bemoans their return every year, disregarding how miraculous their swarms truly are. Many of us are so ignorant to our destruction that we fail to see miracles when they butt against our conveniences.

The mayfly and the public’s disgust response to them helped me understand my peers’ rejection as not being representative of who I am and my story, but a factor of their fears. When my teacher sat me on the couch, I became the embodiment of an uncomfortable truth, an uncomfortable truth also found in the mayfly.

Mayflies, Ephemeroptera, a name of Greek origin meaning “to live one day.” It is true that they only live a blink in the wind, but they live several years at the bottom of our lakes and streams. They make homes for themselves by burrowing in the sediment, toiling every day for the moment that they fly in the setting sun, dancing under street or moonlight, looking for what we call love before they surrender to the web of life. What we see in the morning is long past their opus, as they bravely wait for what will be done. They taught me to not fear the brevity of life if there’s love at the end of my labours. Every year when I see their swarms, I am reminded that strength is navigating your fragility and if given a chance, life can heal.

Leave a Reply